Intro

In the previous post we explored a more intuitive way to view the problem. In this post we’ll code the brute force algorithm and focus a little more on the time complexity details.

Recursion Intro

With recursion it’s all about the recursive leap of faith and thinking in a lazy manner. It’s really hard to solve the problem as a whole however the subproblems are not too bad to solve.

Input: s = “applepenapple”, wordDict = [“apple”,“pen”]

It’s not actually to hard to imagine that we can code something where we eventually realize that “apple” is part of s, then in order to see if the full string can be segmented we’d just need to determine if “penapple” can also be segmented. The first part is not too bad so we’ll take care of that work, trust that the recursion can handle the rest.

If we eventually reach the case where our string is empty that means that we were able to continuously chop off the first part of the string. If we ran out of characters it means everything was successfully found in the wordDict.

Understanding the lazy choice is crucial to recursion

Code

def wordBreak(self, s: str, wordDict: List[str]) -> bool:

wordDict = set(wordDict)

N = len(s)

def dfs(word):

# if word is empty we've found a way to cut things up

if not word:

return True

# i = partition index

# start with closest partition

# if it's in our wordDict try and solve the remaining split recursively

# if we didn't return True then that partition didn't work.

# try choosing the next partition

for i in range(N + 1):

if word[0:i] in wordDict and dfs(word[i:]):

return True

return False

return dfs(s)

Analyzing our code with our intution

Analyzing the O(2^N) time complexity

We mentioned in the previous post that the time complexity of this algorithm is O(2^N). To be a little more precise we do need to account for the fact that taking a slice of the word (word[0:i]) also is O(N) complexity. This means in the worst cast scenario our dfs function is called O(N * 2^N) since with each call we’re going to slice. Time complexity is confusing regardless until it is not. If things are still hazy as to why things are the way to are no worries. The editorial to this problem actually had the wrong time complexity. Don’t underestimate the value of understanding the time complexiy and the brute force solutions. Understanding them makes everything else easier since the rest is almost just applying tricks to optimize the brute force.

As a rule of thumb if you notice that your algorithm has the possibility of choosing and not choosing options think O(2^N).

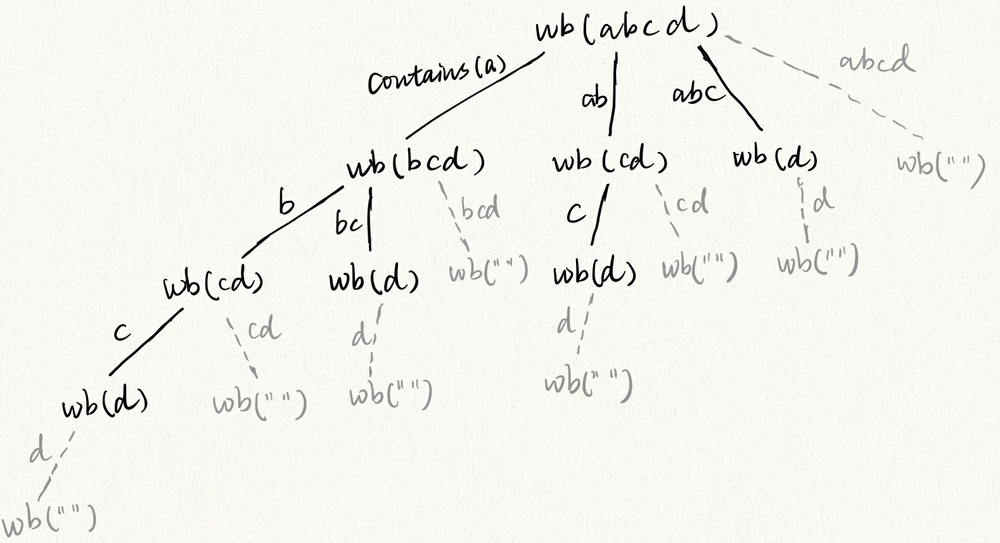

Visualizing the redundant work

The reason the time complexity is so bad is because of the redundant work done. That’s because the calls we make with dfs(secondHalfOfString) we don’t consider have we already answered this question before. If you take a look at this post they break down more of reasoning behing O(2^N). An important takeaway is the visual. Notice that we’re asking determining if the smaller words are valid multiple times. In this decision tree you can see that we calculate is

- dfs(“d”): 4 times = 3 redundant calls

- dfs(“cd”): 2 times = 1 redundant call

So for a string “abcd” we have 4 partitions. 2^4 = 16 calls to dfs. If in those two examples we noticed 4 redundant calls. That means 25% of our time is wasted.

The key is to notice there are many ways we can end up looking at the smaller pieces of the second half of the word many times like in the case of “d” and “cd”.

No redundant work = O(N^3)

One way to think of our algorithm is that we start with the closest partition then grow it until we see something in the wordDict. Once we find a match we recursively try and solve the split that taking the partition creates. If we ignore redundant work then that measns that the number of calls we can make depends on how many unique ways can we view the string.

“bcd” “cd” “d”

""

a | b | c | d |

So our recursive function takes a look at the second half of the question. We look at “a”, recursively we look at “aab” We look at “aa”, recursively we look at “ab” We look at “aaa”, recursively we look at “b” We look at “aaaa”, recursively we look at “”.

If any of the things we look at was found then we need to investigate the recursive call. New substring is a | a | b | We look at “a”, recursively we look at “ab” We look at “aa”, recursively we look at “b” We look at “aaab”, recursively we look at ""

We will not address why looking at all possible substrings has a time complexity of O(N^2) but in this article we’ll take it as a given. Since we’re calculating the substring each time this multiplies O(N) to the complexity however you could devise an algorithm that avoids this splicing cost.

With memoization: $$ O(N^3) $$

Note that we’re not actually looking at all possbile substrings. Our algrithm chooses a partition at each step

our recursion only really looks at the suffixes