Introduction

Warning: Code may not be 100% compilable but it should be close. I was making changes along the way so although at one point it passed the test cases it might not now.

In our previous posts we learned how to reverse rows and columns which we can use to solve Flip Matrix in a brute force way.

Calculating sum of a quadrant

Part of the flip matrix problem requires us to calculate the upper left quadrant’s sum. At first this sounds complicated but it is not too bad. A quadrant is just a quarter of the matrix. This means we know that the width is half of the full width and the height is half of the full height. I think visualizing it as indicies could make things more clear.

[112, 42, 83, 119],

[56, 125, 56, 49],

[15, 78, 101, 43],

[62, 98, 83, 108]

The upper right quadrant is just deleting the bottom half rows and the last two columns

[112, 42],

[56, 125]

This means we’re iterating from rows 0 -> half of the total rows, and cols 0 -> half of the total cols.

sum = 0

for r in range(N // 2):

for c on range(N // 2):

sum += matrix[r][c]

Again why not use list comprehensions, maybe you like or maybe you don’t but it’s always an option. We just ensure that the range of both rows and cols are half.

total_sum = sum(matrix[r][c] for c in range(len(cols) // 2) for r in range(len(rows) // 2))

Therefore, viewing the quadrants as a subset of the matrix that you can easily iterate over makes it easier to reason about.

Putting it all together

for r in range(rows):

for c in range(cols):

# at this time none are reversed

sum1 =

only_row_reversed = reverse_row(r, matrix)

only_col_reversed = reverse_col(c, matrix)

# both_reversed = reverse_row(r, only_col_reversed)

both_reversed = reverse_col(r, only_row_reversed)

Trying all possible combinations

Well how many ways can we do this?

- We can reverse the row

- We can reverse the column

- We can reverse both

- We can reverse none

This lovely idea of choosing all possibilities leads us to backtracking and combinations. For every possible row and column we need to try those 4 possibilities. One loop is not enough for this. We need the nested loops since there is an entanglement that we can choose to reverse both row and column.

# wont work

for r in range(rows):

reverse_row(r)

for c in range(cols):

reverse_col(c)

The code above won’t allow us to try the situation where row 0 and col 0 are reversed at the same time!

for r in range(rows):

for c in range(cols):

# at this time none are reversed

sum_quadrant(matrix)

only_row_reversed = reverse_row(r, matrix)

sum_quadrant(only_row_reversed)

only_col_reversed = reverse_col(c, matrix)

sum_quadrant(only_col_reversed)

# alternative: both_reversed = reverse_row(r, only_col_reversed)

both_reversed = reverse_col(r, only_row_reversed)

sum_quadrant(both_reversed)

Nested loops in this fashion don’t cut it as well. The reason why is because it is unable to build up from the previous reversals. With this nested loop we start out at (0,0). Trying all possible optins that we have at this point means:

- Flip neither the 0th row and 0th column

- Flip just row 0

- Flip just column 0

- Flip row 0 then column 0

- Flip column 0 then row 0

After trying all those choices we need to continue building on top of those options. For example, If we’ve just flipped the first row alone then on the next iteration we’d like to keep that choice and continue building. What if the right answer wants us to flip the first row and last row for the optimal solution. A nested loop like this won’t allow us to do that since the state of only_row_reversed is lost on the next iteration.

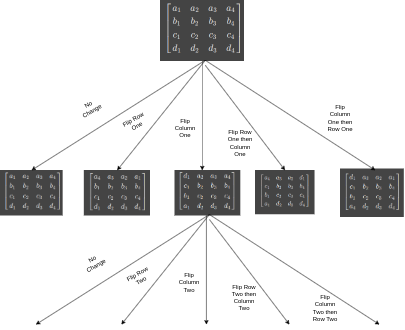

Building a Tree

This leads us to recursion. Recursion is great at this idea of repeating work on a new state. In our problem, we want to repeat our choices of flipping and not flipping with the previous choices we’ve made. We won’t touch on this too much in this article but take a look at generate parentheses and N Queens Problem and sudoku. These all share the idea that we’re manipulating the state and investigating this further. Our state tree will look something like this.

Once we perform an operation we need to continue down that route and apply the exact same changes.

Disclaimer: This code worked for some test cases but not thouroughly tests

def flipMatrix(matrix):

rows = len(matrix)

cols = len(matrix[0])

results = []

def dfs(r, c, matrix):

print(r,c)

only_row_reversed, only_col_reversed, both_reversed = 0,0,0

if r >= rows or c >= cols:

return

if r < rows:

only_row_reversed = reverse_row(r, matrix)

sum_row_reverse = sum_quadrant(only_row_reversed)

results.append(sum_row_reverse)

dfs(r + 1, c, only_row_reversed)

dfs(r + 1, c, matrix)

if c < cols:

only_col_reversed = reverse_column(c, matrix)

sum_col_reverse = sum_quadrant(only_col_reversed)

results.append(sum_col_reverse)

dfs(r, c + 1, only_col_reversed)

dfs(r, c + 1, matrix)

dfs(0,0, matrix)

print(max(results))

return max(results)

Breaking down the Backtracking Logic

I think thinking about things recursively the code makes sense. If you’re still able to, reverse the rows and columns then both. The challenging part with recursion and backtracking is that when you try to think about things further then the code gets confusing. That could be because its hard to see how the state is changing with some recursive code.

In this code because our very first recursive call is reversing a row it greedily tries all possible combinations with the reversing the rows. We’ll continue reverse all rows until we have done that for all rows, now the first if condition is false since we’re at a state where can no longer reverse rows since we’ve already reversed them all. Now we can move toward the second if statement and similarly since the first recursive call is the one where we reverse the column, we greedily do so until we can’t anymore. This leads us to the first leaf we’ll reach which represents the reversal of all rows, followed by reversals of all columns. At this point we save the sum of this matrix’s upper quadrant and return.

With recursion there is lots of symmetry. We reversed all rows, then all columns and when we return we “wake up” at the state where we have one last column decision to make. In our code that is the line with dfs(r + 1, c, matrix). At this point we’ve already tried to reverse the last column so on this instance we choose not to reverse the last column.

The symmetry is that that although we applied the reversal of the columns last, as our recursion unwinds we’ll be performing the second recursive call for our columns before the second recrusive call of our rows.